The number of companies using psychometric testing is growing, but how should it be managed to maximise its effect and avoid psychometric terror for its subjects?

“After that appalling experience, I was stuck in bed for three days,” said one executive we interviewed while gathering the feedback of professionals exposed to psychometric testing. A great deal of emotion flowed from the interviews. Even though psychometric testing has become commonplace, it is far from being popular, especially among those who are subjected to it.

The reasons for the nervousness range from poor preparation and explanation, draconian testing conditions to feedback problems, ranging from “none at all” to “still waiting” and even “psychologically destabilising”. In addition, some of the testing approaches, such as multiple choice questionnaires are not well received in all cultures.

Psychometric tests are used to identify an employee’s aptitudes, personality traits or ability by focusing on verbal and numerical reasoning and other capabilities such as self-motivation or stamina. Companies increasingly use them to make hiring decisions and significant internal promotions. But when such testing is managed badly, it can have damaging consequences.

Deeply scarred

Elena, a Czech-American executive from the engineering industry and Pierre, a Frenchman in hospitality had deeply scarring experiences.

Elena had initially had good experiences with psychometric testing, until she met with a 360 assessment that had been designed to undermine her by a colleague envious of a prestigious position she’d been offered. This latest assessment had been “ordered” by the colleague and she later discovered that people who did not know her had been asked to say destructive things about her. Elena walked into the trap and was deeply damaged by it.

Elena’s next encounter with psychometric testing came as part of the process of evaluation for a very senior role in another industry sector. From the outset, she was bombarded with maths and language testing similar to what she had done at SAT and GMAT level. In her mid-forties, she felt that the content was hardly relevant to a senior role in which leadership and soft communication skills are far more pertinent. She also had to tackle a 50-page case study and submit herself to a two-hour interview with a psychologist. She subsequently spent two days in bed feeling drained and bewildered, with a sense of outrage at having been demeaned on so many fronts. Almost a month later, she hadn’t received any feedback.

In Pierre’s case, he was used as a guinea pig for a different type of assessment, which had been recommended by a new arrival in the company. The assessment was administered by a new member of the HR team, who had not done his research, and simply showed up and gave the test to Pierre, with no context. The test focused very strongly on psychological aspects, and hardly at all on behaviour and relationships.

Pierre’s sense was that it was neither relevant nor appropriate for a senior role. He was uncomfortable during the test, but this was nothing compared to how he felt afterwards. The report from the assessment was sent, without any human interaction, straight to Pierre, as well as to his boss and several other people within the organisation. This was done on a Friday evening when there was no recourse to internal discussion or debate.

On reading the report, Pierre found it to be “amazingly violent” and “an excessively harsh personality judgment”. He was so shocked at the way the feedback was given, that he not only asked his wife for a considered opinion (after two sleepless nights!) but also consulted with a labour lawyer. Both were as dumbfounded as he was.

Pierre later described the unorthodox methods used to produce the report. The examiners used his “ability” to explain how to reproduce a drawing to judge his capacity to “work with precision”. This assessment was the beginning of the end for Pierre at his company and he still wonders whether it was done to push him out.

“The best development feedback of my career”

Managed correctly, however, psychometric testing can be beneficial to the organisation and the employee. Christian, a 41-year old French national with a senior role in a global pharmaceutical company attended a workshop with six other internal candidates. He was given written and interview tests and feedback was immediate and thorough, given by an extremely interactive consultant, who observed and managed his interactions at every stage. He still calls it “the best development feedback of my whole career”. He also used it to form his own development plan.

However, there was one part that, while clear to Christian via internal networks, had not been made known to the candidates during the process. The simple scoring system (1-4) and its implications did not give transparent feedback to the participants about what would happen next. They were told if they had “passed or failed”, but not given any context about what that might mean. In fact, it was necessary to have a “well above average” overall score, as Christian had obtained, in order to be considered for the leadership pool he was trying to enter. Not all had achieved this, despite “passing”, and so disappointment was inevitable at some point in their future.

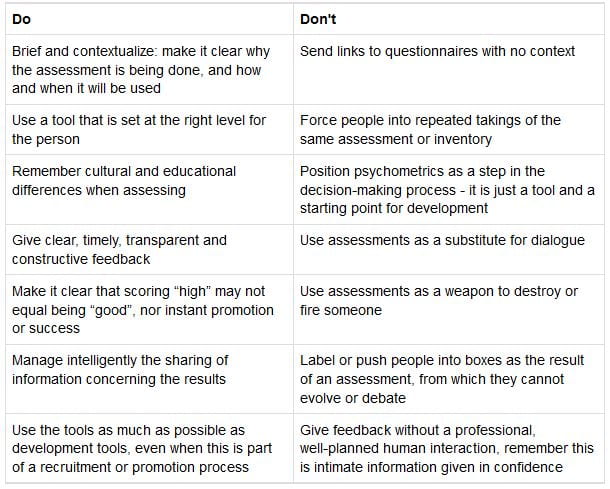

Seven “Do’s” and “Don’t’s” for all managers to consider

Handle With Care

The success of psychometric testing, whether used internally or externally, depends more than anything on how it is handled. A well-designed test, poorly managed, has as much chance of being a disastrous turn-off as a badly designed one does. The human factor is something we should ignore at our peril, despite the handy nature of these numerically measured tests. When well designed and used, they can be a delightful opportunity to explore development potential, as in Christian’s story. If they are well designed but poorly managed, we start to get unhappy candidates, and when both sides go wrong, we damage people, possibly for life. This is not to be taken lightly and all should learn from this ̶ candidates and HR professionals alike.

Antoine Tirard is a talent management advisor and the founder of NexTalent. He is co-author of Révélez vos Talents, a guide of psychometric tools. You can follow him on Twitter @antirard1. Claire Lyell is the founder of Culture Pearl and an expert in written communication across borders and languages. You can follow her on Twitter @CulturePearlC