Can Big Food help us fight obesity?

Everyone with an interest in health—or just with eyes open—knows that obesity has reached epidemic levels, and not just in the Western world. More than 50 percent of women in Kuwait, Kiribati, Micronesia, Libya, Qatar, Tonga and Samoa are obese (compared with 34 percent of women in the United States).

Now the business world is starting to pay attention. A McKinsey report published in November 2014 estimated the economic impact of obesity at $2 trillion annually, or 2.8% of global GDP, almost equal to the global cost of war and terrorism.

We all know that overcoming obesity will require a multi-pronged approach and engagement from all, including the food industry. The problem is that the usual solutions—new taxes, warning labels, restrictions on what food can be served in school lunches—all emphasise health over the pleasure of eating on which the industry is built. These solutions are also seen as compromising our cherished freedom to choose and eat the food that we like. No wonder then that they are bitterly opposed by the food industry in areas ranging from labeling laws to what food can be served in school lunches.

Let them sell broccoli

Certainly, it would be absurd to deny the responsibility of food marketing in the obesity crisis, as I detailed in a review paper published with my longtime colleague Brian Wansink. Yet, in public health, it is almost a matter of faith that “big food” cannot play “any constructive role” in this crisis and that they are just as bad, or perhaps even worse than “big tobacco”.

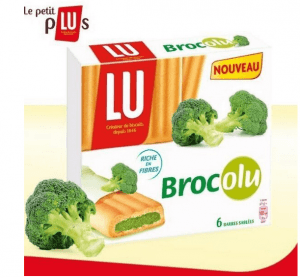

At first blush, it is true that food marketers cannot simply switch to selling just broccoli. We have a biological preference for food that is high in sweet, fat, and salt. And when Mondelez launched Brocolu, its newest healthy snack, it did so on April 1st (a joke, of course).

Still unconvinced? Watch this hilarious television commercial for Crest toothpaste showing, in hidden camera, how kids react to vegetable-based healthy Halloween candies.

Health halos and the limits of food reformulation

Because “big food” companies can’t just switch to selling broccoli, they have invested a lot of effort and science to improve the nutritional quality of the food that people enjoy by removing salt, sugar and fat. This is all good until consumers find out. When people think that food has been “improved” to be healthier (i.e., “processed”), they react badly for business, and badly for healthy eating as well. Some, especially men, reject the “frankenfood” because they cannot believe that food can be both healthy and tasty—and taste is and will remain the number one factor driving food choices.

Others, especially those who are dieting or overweight, adopt the healthier food but eat more of it—a lot more. For example, one of my studies found that people with a normal weight consumed 16% more M&M’s (and those who were overweight 46% more) when the candies were described as “low fat,” yet expected that they had not taken more calories. I call this a “health halo”: If a food has one healthy feature (even if it is loosely related to health, such as “environmentally friendly”), people wrongly assume that this food scores high on all dimensions of healthiness and that it is nonfattening. For example, people often assume that “low-fat” foods are also low in calories when, in reality, the fat has just been replaced by added sugar!

Portion size reduction: A win-win for health and business?

Today’s food portions are now routinely two to three times larger than they used to be. In fast food restaurants, the kid’s cup is larger (at least 25 cl) than what has been considered a regular adult size for the first 60 years of Coca-Cola’s history (19 cl). Not so long ago, 16 oz. (48 cl) used to be a “big size”, “enough to serves 3”’. Now, New York City’s effort to limit single-servings to 16 oz. was invalidated by the state’s Supreme Court.

Supersizing is very profitable. And certainly people should be free to make informed choices and prefer value and taste over health. The trouble is that we don’t realise how large today’s supersized portions have become. In our studies, even trained dieticians underestimated the number of calories of large fast-food meal by more than 50%.

We are all victim of a pernicious visual bias which makes any object that had doubled in size appear to be 50 to 80% bigger, not 100% bigger. Why? To make a long story short, it’s because our eyes are bad at geometry. When estimating the volume of objects, we visually add instead of multiplying the change in height, width, and length. Although increasing the height, width, and length of any object is enough to double its volume (because 1.26*1.26*1.26=2), to our eyes it will only look around 78% bigger (because 26%+26%+26%=78%).

So, what can be done? Unfortunately, teaching intuitive portion estimation is very hard. A good start is to make size and calorie information mandatory everywhere, including on menu boards, for beer, popcorn or vending machines, as the FDA has just mandated. It is also the fair thing to do, even if unfortunately only a few people will pay attention.

A more effective solution is to rely on the fact that people evaluate sizes relatively, not at an absolute level. Simply adding back the old regular size (say, 19cl) to the menu will turn the current “small” size (25cl) into a “medium”, encouraging up to 30% of people to downsize. This will counteract the effects of today’s humongous “double gulp” cups, which make even “supersized” 50cl cups look skimpy.

My favorite solution is to exploit our visual biases to make the regular portions of yesterday look bigger. With my former PhD student Nailya Ordabayeva, we showed that marketers should never downsize their packages or portions by reducing their height, which makes the quantity loss really obvious. Instead, they should reduce all three dimensions proportionally (because our eyes will fail to compound the changes). Even better, marketers should increase packages’ height while strongly reducing their width, just like the 25 cl Red Bull® slim cans that look almost as big as the regular 33cl cans. To the eye, the longer height is not compensated by the smaller diameter which, in reality, has a quadratic effect on volume (remember your high school math!). Using these principles, we helped a food manufacturer downsize their product by 38% without losing perceived value compare to its competitors.

To fight the effects of supersizing, we need to focus on how much people eat, not just on what they eat. If we do that, we will be able to improve public health while preserving the economic health of a vital sector of our industry. Playing with size impression is just the start. With another INSEAD PhD student, Yann Cornil, we are exploring how sensory pleasure can be more effective than health to motivate people to forego supersized portions. Rather than “improving” food, let’s keep the taste that people love but market it in such a way that they will be happier with less, a triple win for public health, business, and eating enjoyment.

Pierre Chandon is a Professor of Marketing at INSEAD and The L’Oréal Chaired Professor of Marketing, Innovation, and Creativity. He is also the Director of the INSEAD-Sorbonne Behavioral Lab.